Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s original stories. Today we’re looking at “Pickman’s Model,” written in September 1926 and first published in the October 1927 issue of Weird Tales. You can read it here.

Spoilers ahead.

“There was one thing called “The Lesson”—heaven pity me, that I ever saw it! Listen—can you fancy a squatting circle of nameless dog-like things in a churchyard teaching a small child how to feed like themselves? The price of a changeling, I suppose—you know the old myth about how the weird people leave their spawn in cradles in exchange for the human babes they steal. Pickman was shewing what happens to those stolen babes—how they grow up—and then I began to see a hideous relationship in the faces of the human and non-human figures.”

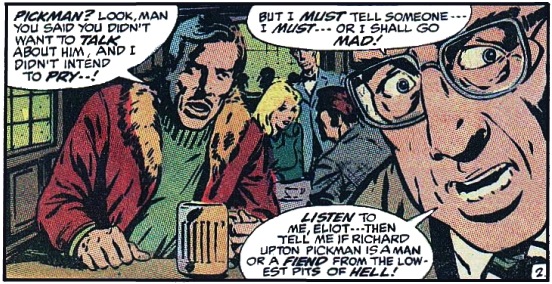

Summary: Our narrator Thurber, meeting his friend Eliot for the first time in a year, explains his sudden phobia for the Boston subway and all things underground. It’s not crazy—he has good reason to be anxious, and to have dropped their mutual acquaintance, the artist Richard Upton Pickman, and yes, the two things are related.

Thurber didn’t drop Pickman because of his morbid paintings, as did other art club members. Nor did he hold with an amateur pathologist’s idea that Pickman was sliding down the evolutionary scale, perhaps due to abnormal diet. No, even now, Thurber calls Pickman the greatest painter Boston ever produced—an uncanny master of that “actual anatomy of the terrible and physiology of fear” which mark the true artist of the weird.

Pickman’s disappeared, and Thurber hasn’t informed the police of a North End house the artist rented under an assumed name. He’s sure he could never find the place again, nor would he try, even in broad daylight.

Thurber became Pickman’s eager disciple while planning a monograph on weird art. He viewed work that would have gotten Pickman kicked out of the club and listened to theories that would have landed Pickman in a sanitarium. Having thus earned Pickman’s trust, he’s invited to the artist’s secret studio in Boston’s North End.

The North End is the place for a really courageous artist, Pickman contends. So what if it’s become a slum swarming with “foreigners?” It’s old enough to harbor generations of ghosts. Houses still stand that witnessed the days of pirates and smugglers and privateers, people who dug a whole network of tunnels to escape their Puritan persecutors, people knew how to “enlarge the bounds of life”! Oh, and there were witches, too. Like Pickman’s four-times-great-grandmother, who was hanged during the Salem panic.

Pickman leads Thurber into the oldest and dirtiest alleys he’s ever encountered. Thurber’s amazed to see houses from before Cotton Mather’s time, even archaic PRE-GAMBREL rooflines supposedly extinct in Boston. The artist ushers Thurber inside and into a room hung with paintings set in Puritan times. Though there’s nothing outré in their backgrounds, the figures—always Pickman’s forte—oppress Thurber with a sense of loathsomeness and “moral fetor.” They’re chiefly bipedal(ish) monstrosities of canine cast and rubbery texture, munching on and fighting over “charnel booty.”. The worst paintings imply the ghoulish beasts are related to humans, perhaps descended from them, and that they exchange their young for babies, thus infiltrating human society. One shows ghouls teaching a human child to feed as they do. Another shows a pious Puritan family in which the expression of one son reflects “the mockery of the pit.” This awful figure, ironically, resembles Pickman himself.

Now, Eliot saw enough of Thurber during WWI to know he’s no baby. But when Pickman leads him into a room of paintings set in contemporary times, he reels and screams. Bad enough to imagine ghouls overrunning the world of our ancestors; it’s too much to picture them in the modern world! There’s a depiction of a subway accident, in which ghouls attack people on the platform. There’s a cross-section of Beacon Hill, through which ghouls burrow like ants. Ghouls lurk in basements. They sport in modern graveyards. Most shockingly, somehow, they crowd into a tomb, laughing over a Boston guidebook that declares “Holmes, Lowell and Longfellow lie buried in Mount Auburn.”

From this hellish gallery, Pickman and Thurber descend into the cellar. At the bottom of the stairs is an ancient well covered with a wooden disc—yes, once an entrance into that labyrinth of tunnels Pickman mentioned. They move on to a gas-lit studio. Unfinished paintings show penciled guidelines that speak to Pickman’s painstaking concern for perspective and proportion—he’s a realist, after all, no romanticist. A camera outfit attracts Thurber’s attention. Pickman says he often works from photos. You know, for his backgrounds.

When Pickman unveils a huge canvas, Thurber screams a second time. No mortal unsold to the Fiend could have depicted the ghoul that gnaws a corpse’s head like a child nibbling candy! Not with such horrific realism, as if the thing breathed. Conquering hysterical laughter, Thurber turns his attention to a curled photograph pinned to the canvas. He reaches to smooth it and see what background the terrible masterpiece will boast. But just then Pickman draws a revolver and motions for silence. He goes into the cellar, closes the studio door. Thurber stands paralyzed, listening to scurrying and a groping, furtive clatter of—wood on brick. Pickman shouts in gibberish, then fires six shots in the air, a warning. Squeals, thud of wood on brick, well cover back over well!

Returning, Pickman says the well’s infested with rats. Thurber’s echoing scream must have roused them. Oh well, they add to the atmosphere of the place.

Pickman leads Thurber back out of the ancient alleys, and they part. Thurber never speaks to the artist again. Not because of what he saw in the North End house. Because of what he saw the next morning, when he pulled from his pocket that photo from the huge canvas, which he must have convulsively stowed there in his fright over the rat-incident.

It shows no background except the wall of Pickman’s cellar studio. Against that stands the monster he was painting. His model, photographed from life.

What’s Cyclopean: Nothing—but on the architecture front we do get that pre-gambrel roof-line. Somewhere in the warrens below that roof-line is an “antediluvian” door. I do not think that word means what you think it means.

The Degenerate Dutch: Pickman boasts that not three Nordic men have set foot in his iffy neighborhood—as if that makes him some sort of daring explorer in the mean streets of Boston. But perhaps we’ll let that pass: he’s a jerk who likes shocking people, and “to boldly go where lots of people of other races have already been” isn’t particularly shocking.

Mythos Making: Pickman will make an appearance in “Dreamquest of Unknown Kadath”—see Anne’s commentary. Eliot and Upton are both familiar names, though common enough in the area that no close relation need be implied—though one does wonder whether the Upton who killed Ephraim Waite was familiar with these paintings, which seem of a kind with Derby’s writing.

Libronomicon: Thurber goes on about his favorite fantastical painters: Fuseli, Dore, Sime, and Angarola. Clark Ashton Smith is also listed as a painter of some note, whose trans-Saturnian landscapes and lunar fungi can freeze the blood (it’s cold on the moon). The books all come from Pickman’s rants: he’s dismissive of Mather’s Magnalia and Wonders of the Invisible World.

Madness Takes Its Toll: More carefully observed psychology here than in some of Lovecraft’s other stories—PTSD and phobia for a start, and Pickman has… what, by modern standards? Antisocial personality disorder, narcissistic p.d., something on that spectrum? Or maybe he’s just a changeling.

Anne’s Commentary

You know what I want for Christmas? Or tomorrow, via interdimensional overnight delivery? A great big gorgeous coffee-table book of Richard Upton Pickman’s paintings and sketches. Especially those from his North End period. I believe he published this, post-ghoulishly, with the Black Kitten Press of Ulthar.

Lovecraft wrote this story shortly after “Cool Air,” with which it shares a basic structure: First-person narrator explaining a phobia to a second-person auditor. But while “Cool Air” has no definite auditor and the tone of a carefully considered written account, “Pickman’s Model” has a specific if vague auditor (Thurber’s friend Eliot) and a truly conversational tone, full of colloquialisms and slang. Among all Lovecraft’s stories, it arguably has the most immediate feel, complete with a memory-fueled emotional arc that rises to near-hysteria. Poor Thurber. I don’t think he needed that late-night coffee. Xanax might do him more good.

“Model” is also product of a period when Lovecraft was working on his monograph, Supernatural Horror in Literature. It’s natural that it should continue—and refine—the artistic credo begun three years before in “The Unnamable.” Pickman would agree with Carter that “a mind can find its greatest pleasure in escapes from the daily treadmill,” but I don’t think he’d hold with the notion that something could be so “infamous a nebulosity” as to be indescribable. Pickman’s own terrors are the opposite of nebulous, only too material. Why, the light of our world doesn’t even shy from them—ghouls photograph very nicely, thank you, and the artist who can do them justice must devote attention to perspective, proportion and clinical detail. Tellingly, one more piece comes from the fruitful year of 1926: “The Call of Cthulhu,” in which Lovecraft begins in earnest to create his own “stable, mechanistic and well-established horror-world.”

Can we say, then, that “Model” is a link between Lovecraft’s “Dunsanian” tales and his Cthulhu Mythos? The Dreamlands connection is clear, for it’s Pickman himself, who will appear in 1927’s Dream Quest of Unknown Kadath as a fully realized and cheerful ghoul, gibbering and gnawing with the best of them. I’d contend that the North End studio stands within an interzone between the waking and dreaming worlds, as Kingsport of the mile-high cliffs may, and also the Rue d’Auseil. After all, those alleys hold houses that supposedly no longer stand in Boston. And Thurber’s sure he could never find his way back to the neighborhood, just as our friend back in France could never again find the Rue.

On the Mythos end of the connection, we again have Pickman himself, at once a seeker of the weird and an unflinching, “almost scientific” realist. He has seen what he paints—it’s the truth of the worlds, no fantasy, however much the majority of people might want to run from and condemn it. Thurber, though a screamer, does show some courage in his attitude toward the North End jaunt—he’s the rare Lovecraft protagonist who doesn’t cling to the comfort of dream and/or insanity as explanations for his ordeal. He’s not crazy, even if he is lucky to be sane, and he has plenty of reason for his phobias.

Of course some (like Eliot?) could say Thurber’s very conviction is proof of insanity. And wouldn’t the ghouls just laugh and laugh about that?

On the psychosexual front, it’s interesting that Lovecraft does not want to go there with humans and ghouls. Things will be different when we get to Innsmouth a few years later; he will have worked himself to the sticking point and acknowledged that the reason for the infamous Look is interbreeding between Deep Ones and humans. In “Model,” gradations from man to ghoul (practically a monkey-to-Homo sapiens parade) are called an evolution. If Thurber’s intuition is correct, that ghouls develop from men, then is it a reverse evolution, a degradation? Or are ghouls “superior,” winners by virtue of that cruel biological law we read about in “Red Hook”?

Anyhow, ghouls and humans do not have sex in “Pickman’s Model: The Original.” They intersect, neatly, via the folklore-approved method of changelings—ghoul offspring exchanged for human babies, which ghouls snatch from cradles, those rocking surrogate wombs they then fill with their own spawn. “Pickman’s Model: The Night Gallery Episode” is less squeamishly symbolic. It gets rid of boring old Thurber and gives Pickman a charming female student, who falls in love with him, natch. No changelings here, just a big virile ghoul who tries to bear the student off to his burrow-boudoir. Pickman interferes, only to be borne off himself. Hmm. Bisexual ghouls?

Looking outside, I see more snow arriving, not the interdimensional mail person. When’s my Pickman book going to arrive? I hope I don’t have to dream my way to Ulthar for it. Although it is always cool to hang with the cats.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

We’ve discussed, in an earlier comment thread, whether Lovecraft’s shocking endings are really meant to be shocking. Chalk this one up as strong evidence against: the ending is telegraphed in the title. The first time Thurber shudders over the lifelike faces in Pickman’s ghoulish portraits, it doesn’t take a genre savvy genius to figure that he might be drawing from, I don’t know, a model? Instead, this one is all about the psychology.

And what interesting psychology! Thurber mentions, to his friend Eliot, their shared experiences “in France” as proof of his usual unflappability. So we’ve got a World War I vet here. That painting of the ghouls tearing down Boston—he’s seen cities destroyed, he knows that horror. But this, the place he’s living now, is supposed to be safe. Boston didn’t get invaded during the war, probably hasn’t been attacked within his lifetime. And now he learns, not that there are terrible, uncaring forces in the world—he knew that already—but that they’re on his home soil, tunneling under his feet, ready to come out and devour every semblance of safety that remains.

No wonder he drops Pickman. I’d have done a damn sight more than that—but it’s 1926, and it’ll be decades yet before horror is something you talk about openly, even when its dangers are all too real.

I’m starting to notice a taxonomy of “madness” in these stories. First we have the most generic sort of story-convenient madness—more poetic than detailed, likely to make people run wild, and not much like any actual mental condition. Sometimes, as in “Call of Cthulhu,” it’s got a direct eldritch cause; other times it’s less explicable. Then we have the madness that isn’t—for example Peaslee’s fervent hope, even while asserting normalcy, that his alien memories are mere delusion. (Actually, Lovecraft’s narrators seem to wish for madness more often than they find it.) And finally, we have stories like this one (and “Dagon,” and arguably the Randolph Carter sequence): relatively well-observed PTSD and trauma reactions of the sort that were ubiquitous in soldiers returning from the first World War. Ubiquitous, and as far as I understand it, rarely discussed. One suspects a good portion of Lovecraft’s appeal, at the time, was in offering a way to talk about the terrible revelations that no one cared to acknowledge.

This also explains why he seemed, when I started reading his stuff, to write so well about the Cold War as well. Really, we’ve been recapitulating variations on an eldritch theme for about a century now.

A friend of mine, a few years younger than me, went on a cross-country road trip—and one night camped out at the edge of a barbed-wire-fenced field with big concrete cylinders. ICBM silos. He thought it was an interesting anecdote, and couldn’t understand why I shuddered. I’d rather sleep over an open ghoul pit.

Or maybe it’s the same thing. You know the horror is down there, but it’s dangerous to pay it too much attention. Speak too loudly, let your fear show—and it just might wake up and come out, eager to devour the world.

Next week, architectural horror of the gambrel variety in “The Shunned House.”

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian novelette “The Litany of Earth” is available on Tor.com, along with the more recent but distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land.” Her work has also appeared at Strange Horizons and Analog. She can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal. She lives in a large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “Geldman’s Pharmacy” received honorable mention in The Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror, Thirteenth Annual Collection. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” is published on Tor.com, and her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen. She currently lives in a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island.